This article is about the practice of shamanism; for other uses, see Shaman (disambiguation).

Shamanism refers to a range of traditional beliefs and practices concerned with communication with the spirit world. There are many variations in shamanism throughout the world, though there are some beliefs that are shared by all forms of shamanism:

Its practitioners claim the ability to diagnose and cure human suffering and, in some societies, the ability to cause suffering. This is believed to be accomplished by traversing the axis mundi and forming a special relationship with, or gaining control over, spirits. Shamans have been credited with the ability to control the weather, divination, the interpretation of dreams, astral projection, and traveling to upper and lower worlds. Shamanistic traditions have existed throughout the world since prehistoric times.

Some anthropologists and religious scholars define a shaman as an intermediary between the natural and spiritual world, who travels between worlds in a state of trance. Once in the spirit world, the shaman would commune with the spirits for assistance in healing, hunting or weather management. Ripinsky-Naxon describes shamans as, "People who have a strong interest in their surrounding environment and the society of which they are a part."

Other anthropologists critique the term "shamanism", arguing that it is a culturally specific word and institution and that by expanding it to fit any healer from any traditional society it produces a false unity between these cultures and creates a false idea of an initial human religion predating all others. However, others say that these anthropologists simply fail to recognize the commonalities between otherwise diverse traditional societies.

Shamanism is based on the premise that the visible world is pervaded by invisible forces or spirits that affect the lives of the living. In contrast to animism and animatism, which any and usually all members of a society practice, shamanism does not require specialized knowledge or abilities. It could be said that shamans are the experts employed by modern, animists or animist communities. Shamans are, however, often organized into full-time ritual or spiritual associations, as are priests, being the unordained priests of instinct.

The spirits can play important roles in human lives.

The shaman can control and/or cooperate with the spirits for the community's benefit.

The spirits can be either good or bad.

Shamans get into a trance by singing, dancing, taking entheogens, meditating and drumming.

Animals play an important role, acting as omens and message-bearers, as well as representations of animal spirit guides.

The shaman's spirit leaves the body and enters into the supernatural world during certain tasks.

The shamans can treat illnesses or sickness.

Shamans are healers, psychics, gurus and magicians.

The most important object is the drum; it symbolizes many things to a shaman. Sometimes drums are decorated with rattles, bells or bones to represent different spirits and animals, depending on the region and the community. Etymology

The shaman may fulfill multiple functions in the community,, or inversely, the departing soul of the newly-dead. They may also serve the community by maintaining the tradition through memorizing long songs and tales.

Function

Shamans act as "mediators" in their culture.

Mediator

In some cultures there may be additional types of shamans, who perform more specialized functions. For example, among the Nanai people, a distinct kind of shaman acts as a psychopomp.). Among the Huichol shamans, there are two categories of shamans. This demonstrates the differences of shamans even within a single tribe.

Distinct types of shamans

In tropical rainforests, resources for human consumption are easily depletable. In some rainforest cultures, such as the Tucano, a sophisticated system exists for the management of resources, and for avoiding the depletion of these resources through overhunting. This system is conceptualized in a mythological context, involving symbolism and, in some cases, the belief that the breach of hunting restrictions may cause illness. As the primary teacher of tribal symbolism, the shaman may have a leading role in this ecological management, actively restricting hunting and fishing think that the shaman is able to "release" game animals (or their souls) from their hidden abodes.

Ecological aspect

The plethora of functions described in the above section may seem to be rather distinct tasks, but some important underlying concepts join them.

Soul concept

The beliefs related to spirits can explain many phenomena too, for example, the importance of storytelling, or acting as a singer, can be understood better if we examine the whole belief system: a person who is able to memorize long texts or songs (and play an instrument) may be regarded as having achieved this ability through contact with the spirits.

Spirits

The word "shaman" refers to "one who knows":

Knowledge

Practice

In the world's shamanic cultures, the shaman plays a priest-like role; however, there is an essential difference between the two, as Joseph Campbell describes:

"The priest is the socially initiated, ceremonially inducted member of a recognized religious organization, where he holds a certain rank and functions as the tenant of an office that was held by others before him, while the shaman is one who, as a consequence of a personal psychological crisis, has gained a certain power of his own." (1969, p. 231)

A shaman may be initiated via a serious illness, by being struck by lightning and dreaming of thunder to become a Heyoka, or by a near-death experience (e.g., the shaman Black Elk), or one might follow a "calling" to become a shaman. There is usually a set of cultural imagery expected to be experienced during shamanic initiation regardless of the method of induction. According to Mircea Eliade, such imagery often includes being transported to the spirit world and interacting with beings inhabiting the distant world of spirits, meeting a spiritual guide, being devoured by some being and emerging transformed, and/or being "dismantled" and "reassembled" again, often with implanted amulets such as magical crystals. The imagery of initiation generally speaks of transformation and the granting powers to transcend death and rebirth.

In some societies shamanic powers are considered to be inherited, whereas in other places of the world shamans are considered to have been "called" and require lengthy training. Among the Siberian Chukchis one may behave in ways that "Western" bio-medical clinicians would perhaps characterize as psychotic, but which Siberian peoples may interpret as possession by a spirit who demands that one assume the shamanic vocation. Among the South American Tapirape shamans are called in their dreams. In other societies shamans choose their career. In North America, First Nations peoples would seek communion with spirits through a "vision quest"; whereas South American Shuar, seeking the power to defend their family against enemies, apprentice themselves to accomplished shamans. Similarly the Urarina of Peruvian Amazonia have an elaborate cosmological system predicated on the ritual consumption of ayahuasca. Coupled with millenarian impulses, Urarina ayahuasca shamanism is a key feature of this poorly documented society[1].

Putatively customary shamanic "traditions" can also be noted among indigenous Kuna peoples of Panama, who rely on shamanic powers and sacred talismans to heal. As such, they enjoy a popular position among local peoples.

Note: The Lakota tradition (which includes the Heyoka and Black Elk, mentioned above) are not really shamanic. There is a big difference between the Lakota culture and shamanic cultures. In shamanic cultures there is the use of psycho-active substances (peyote, fly agaric, psilocybin, etc.) In the Lakota culture pain is often used instead of psychoactive plants. While a Siberian shaman would use fly agaric, a Lakota medicine man would do a sun dance. The Lakota medicine people have some bias against the use of psychoactive plants.

Initiation and learning

Shamanic illness, also called shamanistic inititatory crisis, is a psycho-spiritual crisis, usually involuntary, or a rite of passage, observed among those becoming shamans. The episode often marks the beginning of a time-limited episode of confusion or disturbing behavior where the shamanic initiate might sing or dance in an unconventional fashion, or have an experience of being "disturbed by spirits". The symptoms are usually not considered to be signs of mental illness by interpreters in the shamanic culture; rather, they are interpreted as introductory signposts for the individual who is meant to take the office of shaman (Lukoff et.al, 1992). Similarities of some shamanic illness symptoms to the kundalini process have been often noted [2]. The significant role of initiatory illnesses in the calling of a shaman can be found in the detailed case history of Chuonnasuan, the last master shaman among the Tungus peoples in Northeast China (Noo and Shi, 2004).

Shamanic illness

The shaman plays the role of healer in shamanic societies; shamans gain knowledge and power by traversing the axis mundi and bringing back knowledge from the heavens. Even in western society, this ancient practice of healing is referenced by the use of the caduceus as the symbol of medicine. Often the shaman has, or acquires, one or more familiar helping entities in the spirit world; these are often spirits in animal form, spirits of healing plants, or (sometimes) those of departed shamans. In many shamanic societies, magic, magical force, and knowledge are all denoted by one word, such as the Quechua term "yachay".

While the causes of disease are considered to lie in the spiritual realm, being effected by malicious spirits or witchcraft, both spiritual and physical methods are used to heal. Commonly, a shaman will "enter the body" of the patient to confront the spirit making the patient sick, and heal the patient by banishing the infectious spirit. Many shamans have expert knowledge of the plant life in their area, and an herbal regimen is often prescribed as treatment. In many places shamans claim to learn directly from the plants, and to be capable of harnessing their effects and healing properties only after obtaining permission from its abiding or patron spirit. In South America, individual spirits are summoned by the singing of songs called icaros; before a spirit can be summoned the spirit must teach the shaman its song. The use of totem items such as rocks is common; these items are believed to have special powers and an animating spirit. Such practices are presumably very ancient; in about 368 BCE, Plato wrote in the Phaedrus that the "first prophecies were the words of an oak", and that everyone who lived at that time found it rewarding enough to "listen to an oak or a stone, so long as it was telling the truth".

The belief in witchcraft and sorcery, known as brujeria in South America, is prevalent in many shamanic societies. Some societies distinguish shamans who cure from sorcerers who harm; others believe that all shamans have the power to both cure and kill; that is, shamans are in some societies also thought of as being capable of harm. The shaman usually enjoys great power and prestige in the community, and is renowned for their powers and knowledge; but they may also be suspected of harming others and thus feared.

By engaging in this work, the shaman exposes himself to significant personal risk, from the spirit world, from any enemy shamans, as well as from the means employed to alter his state of consciousness. Certain of the plant materials used can be fatal, and the failure to return from an out-of-body journey can lead to physical death. Spells are commonly used to protect against these dangers, and the use of more dangerous plants is usually very highly ritualized.

Practice and method

Generally, the shaman traverses the axis mundi and enters the spirit world by effecting a change of consciousness in himself, entering into an ecstatic trance, either autohypnotically or through the use of entheogens. The methods used are diverse, and are often used together. Some of the methods for effecting such altered states of consciousness are:

Shamans will often observe dietary or customary restrictions particular to their tradition. Sometimes these restrictions are more than just cultural. For example, the diet followed by shamans and apprentices prior to participating in an Ayahuasca ceremony includes foods rich in tryptophan (a biosynthetic precursor to serotonin) as well as avoiding foods rich in tyramine, which could induce hypertensive crisis if ingested with MAOIs such as are found in Ayahuasca brews.

Drumming

Singing

Fasting

Icaros / Medicine Songs

Listening to music

Sweat lodge

Vision quests / vigils

Dancing

Mariri

Swordsmithing

Use of "power" or "master" plants to induce altered states or aromatics used as incense such as

- Ayahuasca - Quechua for Vine of the Dead; also called yage

Cannabis

Cedar

Datura

Deadly nightshade

Fly agaric

Iboga

Morning glory

Peyote

Psychedelic mushrooms - alluded to euphemistically as holy children by Mazatec shamans such as María Sabina.

Sweetgrass

Sage

Salvia divinorum - sometimes called Diviners' sage

San Pedro cactus - named after (St. Peter), guardian and holding the keys to the gates of heaven, by the Andean peoples; Quechua name: Huachuma

Tobacco Shamanic practice

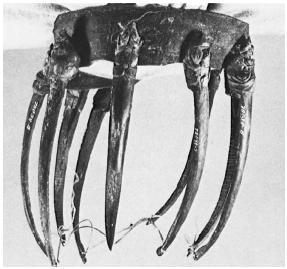

As mentioned above, cultures termed as shaministic can be very different. Thus, shamans may have various kinds of paraphernalia.

Paraphernalia

In many cultures (lots of peoples in Siberia, many Eskimo groups . By being able to interact with a different world at an altered and aware state, the Shaman can then exchange information between the world in which he lives and that in which he has traveled to.

Drum

Drum

While some cultures have had higher numbers of male shamans, others have had a preference for females. Recent archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest known shamans—dating to the Upper Paleolithic era in what is now the Czech Republic—were women.

Gender and sexuality

In some cultures, the border between the shaman and the lay person is not sharp:

The difference is that the shaman knows more myths and understands their meaning better, but the majority of adult men knows many myths, too .

Position

Shamanistic practices are sometimes claimed to predate all organized religions, dating back to the Paleolithic (Shamanism in Prehistory, by Clottes), and certainly to the Neolithic period . Aspects of shamanism are encountered in later, organized religions, generally in their mystic and symbolic practices. Greek paganism was influenced by shamanism, as reflected in the stories of Tantalus, Prometheus, Medea, and Calypso among others, as well as in the Eleusinian Mysteries, and other mysteries. Some of the shamanic practices of the Greek religion later merged into the Roman religion.

The shamanic practices of many cultures were marginalized with the spread of monotheism in Europe and the Middle East. In Europe, starting around 400, the Catholic Church was instrumental in the collapse of the Greek and Roman religions. Temples were systematically destroyed and key ceremonies were outlawed or appropriated. The Early Modern witch trials may have further eliminated lingering remnants of European shamanism (if in fact "shamanism" can even be used to accurately describe the beliefs and practices of those cultures).

The repression of shamanism continued as Catholic influence spread with Spanish colonization. In the Caribbean, and Central and South America, Catholic priests followed in the footsteps of the Conquistadors and were instrumental in the destruction of the local traditions, denouncing practitioners as "devil worshippers" and having them executed. In North America, the English Puritans conducted periodic campaigns against individuals perceived as witches. As recently as the nineteen seventies, historic petroglyphs were being defaced by missionaries in the Amazon. A similarly destructive story can be told of the encounter between Buddhists and shamans, e.g., in Mongolia (See Caroline Humphrey with Urgunge Onon, 1996).

Today, shamanism survives primarily among indigenous peoples. Shamanic practice continues today in the tundras, jungles, deserts, and other rural areas, and also in cities, towns, suburbs, and shantytowns all over the world. This is especially widespread in Africa as well as South America, where "mestizo shamanism" is widespread.

History

Areal variations

While shamanism had a strong tradition in Europe before the rise of monotheism, shamanism remains as a traditional, organized religion in Uralic , Altaic people and Huns; and also in Mari-El and Udmurtia, two semi-autonomous provinces of Russia with large Finno-Ugric minority populations. It was widespread in Europe during the Stone Age

See also Sami shamanism, Huns , Finnish mythology , Tengri and the appropriate parts of Shamanism in Siberia.

Europe

Asia

No comments:

Post a Comment